Pedersen Commitments and Confidential Transactions

Share on:Gradually, as time goes by I intend to make this blog get more and more cypherpunk and today’s tutorial is going to be a game-changer in this journey. We are going to learn about Pedersen commitments (and commitments in general) and we will apply the prior theory of ECC cryptography acquired from Diffie-Hellman key exchange over elliptic curve, hashing functions, eliptic curve digital signature algorithm and Schnorr signature to formalize the concept of confidential transactions.

Information ownership raises important ethical dilemmas. In today’s society information became a valuable resource and is centrally acquired by powerful organizations for close to nothing. We are using online services, mobile payment applications, credit cards, and others often without even realizing we are feeding this huge machine with valuable data. Since we create this data, we should be able to take profits from it. To be the one in control. For that, confidential transactions are a way of storing transaction data on the elliptic curve allowing the third party to verify the validity of this data without them knowing the transaction amounts.

Pedersen commitments

If you are panically afraid of commitments do not worry. This section is about cryptographic commitments! If you recall the hashing functions tutorial you probably know by now that a hashing function can be used to assign a number to anything and if that function is good it is unlikely to find two different things assigned the same number. Such hashing function can be used to form a cryptographic commitment.

For an example of a cryptographic commitment let us imagine a scenario in which Alice and Bob have a bet on who will win the world cup in one of the games where people run and kick an inflated piece of rubber. They do not want to reveal their bet to not influence each other’s choices, at the same time they want to be sure the other party will not change their mind after the winner gets announced. They could form a commitment to a value and share those commitments. Due to the irreversibility of the hashing function, it is not going to be easy to find the matching value, at the same time it is also very unlikely their choices would collide.

| Human | Commitment |

|---|---|

| Alice | cdd878c2097d1af4a1a36a399264acda21b46486c11b1ee1f6fee5019564a5bf |

| Bob | 46bae494a25678968cce8eba0cb5b53bc55d5e0b11d6bbbc7fc82d4425f166be |

Just as a reminder, the commitment by the SHA256 hash function was calculated by simply feeding their committed values into the hash function. Now they simply wait for the world cup to end and the winners get announced. It turns out to be FC Smelly Socks! Now they can both show their inputs to the hash function. Alice’s choice was I bet for smelly socks football club and Bob’s oi oi oi FC sweaty trousers will win! and looks like Alice has won! Bob double-checks by feeding her choice into the SHA256 function and finds a match with cdd878c2097d1af4a1a36a399264acda21b46486c11b1ee1f6fee5019564a5bf and he does not believe she found a way to reverse this hash function so he believes she made this prediction when they both shared the commitments.

$

You probably noticed they decided to write some weird phrase instead of just the official name of the club. Let us denote to be a weird way of writing . That was for the reasons of security as other parties could simply calculate the hash of each football club name to find a match. A way less creative way to achieve that would be to add some random number after the official name and of course, note it down for later! In the context of storing passwords in the database such value is referred to as salt and in the case of cryptographic commitment, we may call it a blinding factor .

The | operator above is the concatenation.

Hashing functions have done the job when it comes to Alice’s and Bob’s bet. However, in terms of commitments, they do have a limitation of not allowing to perform any computation on committed data. The possibility of performing some operations such as addition could be useful, as we will see later. If instead of a simple hashing function we use Pedersen commitments the following properties would hold

The above statement is a homomorphic property of the Pedersen commitments (Pedersen, n.d.). Homomorphic encryption is a type of encryption that allows performing computation on the encrypted data without revealing it. In this case, the computation is the addition and subtraction of the commitments. The homomorphic property seems not so relevant for Alice’s and Bob’s world cup bet however for confidential transactions it is a game-changer! Let us imagine a transaction represented as Pedersen commitment.

Confidential transactions

Back in 2015 Gregory Maxwell introduced the scheme of the confidential transactions based on Pedersen commitments allowing a very private way of storing transactions amounts. Here we will explain this concept in a Mimblewimble way, using Schnorr signature on the excess to prove amounts cancel out. Let us jump right into this concept and imagine that each participant forms their part of the transaction.

What is shown to the third party who keeps the records are values and and what this third party has to check is

which proves no value gets created out of thin air! Let us refer to that as a non-inflation proof. Doing the above computation on the commitment is only possible if it has the homomorphic property. As long as the third party does not know the blinding factors and is not able to know how exactly the values of changes in account balances represented by numbers and .

Such commitment can be implemented using the elliptic curve cryptography by adding curve points corresponding to the blinding factors and amounts by using different generator points.

where generates the blinding factors indicated by and generates the values or amounts indicated by . Having a vanishing difference of two commitments proving the non-inflation can be done by verifying a Schnorr signature with blinding factors as private keys. In the original formalism of confidential transactions, participants would need to pick their blinding factors in such a way that makes them cancel out as well. Given the Mimblewimble approach, the signature can only be valid if generated by which is true only if values cancel out. This can be verified in Python using our regular ECC code as follows

def isTransactionValid(G, inputs_data, outputs_data, p):

inp, inputs_signature = inputs_data

out, outputs_signature = outputs_data

# calculate inputs - outputs

P = inp - out

# check if signature matches proving the difference is 0

inp_s, inp_R = inputs_signature

out_s, out_R = outputs_signature

s_comb = np.mod(inp_s - out_s, p)

valid, _, _ = verify('m', s_comb, G, P, inp_R - out_R, p)

return valid

where G is the generator point. The other generator point is not required during the verification. To understand the notation of this function please check previous the minicurve library.

Example

Let us consider a scenario in which we are a sort of private banking service in which we are in charge of managing people’s transactions. What is so private about our service is the fact that we manage those transactions without knowing the actual amounts being exchanged.

In this example, we will use a small ECC finite field of a prime order to represent a storage space for the transactions. Our users would own outputs which are blinded using the blinding factors as described above. Our banking vault that stores the transactions can be visualized as follows.

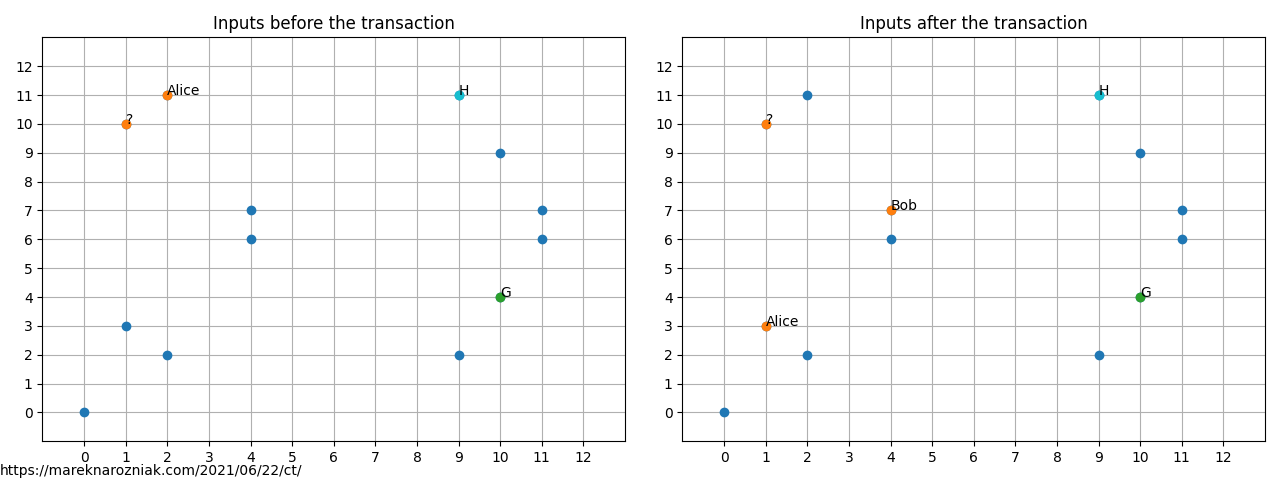

In blue we mark elliptic curve solutions. In green, we have the generator point for the blinding factors and in cyan the generator point for the amounts. In orange, we mark the inputs that are owned by our clients. We can see there is some data there. There are two account balances in the field but hard to make any sense of them (and that’s the point!).

One of the inputs is marked as belonging to Alice. We can imagine Alice has revealed which input belongs to her to perform a transaction with Bob, who is our new client. On the right plot above we see the points after the transaction. Indeed there is a new input we attributed to Bob but we do not know how many coins have been transferred to his account. Alice’s point also changed, meaning that her balance has updated, but what amount, we cannot tell.

As you can see, as verifiers we know nothing, we only check the signature and that proves the net difference is zero, but let us imagine we are Alice and Bob just to explain how this field was generated and how the transaction was created. Since now we are putting ourselves in the shoes of the participants of the transaction we can reveal the confidential information.

It means that Alice has coins and Bob is receiving coins. They are both participants in the transaction thus they both know those values. Alice is blinding her input with value and Bob has just chosen value to blind his newly created input. Only they know those values and they did not share them. Once the transaction is done the input belonging to Alice will be spent thus she needs to also create an output for herself that contains the change of the transaction, she decided to choose the value of to blind her new balance of coins

To perform the transaction each of the participants creates a Schnorr signature using their blinding factors as private keys. Then we combined all the inputs and outputs

and their corresponding signatures as well just as done in the previous tutorial on multisignatures. The corresponding Python code of the process of forming a transaction can be found here. The Schnorr signature can only be valid of terms generated by form infinity point (cancel out) and that is the case if

where is transaction excess. The valid signature proves non-inflation as the difference of inputs and outputs vanishes as well as ownership as only the participant knowing the blinding factor can produce a valid signature. In the original formalism of confidential transactions, participants would need to pick blinding factors in a way to cancel out.

Conclusion

We explained what commitments are in general. Then we extended it to Pedersen commitments to provide the homomorphic property and motivated it by the need for confidential transactions. For the latter, we provided a small example of a transaction with blinded amounts and visualized it on one of our small finite fields from previous tutorials.

Frankly, the fact that this code works and the example transaction is valid is a piece of blind luck. Designing the finite field of prime order with two generator points providing sufficient key space is a huge challenge. I managed to find random nonces for the signature that makes it all work. Please see it as a way to illustrate how it works and not as actual implementation. In cryptography, you should never “hack” your curve, use fields that have been designed and proven by experienced cryptographers.

One might have noticed those transaction participants could introduce negative inputs and thus increase their account balance. This hack is addressed in the Mimblewimble protocol by using bulletproofs to prove the amounts are not negative. I honestly hope to cover the entire Mimblewimble at some point someday. As for this tutorial, I would like to thank @kurt2, @vegycslol, and @phyro for the interesting discussion on the cryptography channel in the grincoin Keybase team. In addition, special thanks again to @phyro and John Tromp for taking their time to read this article and providing comments for the revised version.

The full source code is provided in the public gist repository. As usual, if you find mistakes or have questions please do not hesitate to reach me. Feel free to tweet me and let me know.

- Pedersen, T. P. Non-Interactive and Information-Theoretic Secure Verifiable Secret Sharing. In Advances in Cryptology — CRYPTO ’91 (pp. 129–140). Springer Berlin Heidelberg. 10.1007/3-540-46766-1_9