Satisfiability

Share on:In mathematical logic satisfiability of an expression indicates if there exists an assignment of values, or simply, an input for which such expression yields a particular result. As I like to think about it, it is a logic generalization of the common concept of solving an equation. Determining if a formula is satisfiable is a decidable problem but computationally hard. In this article we are going to focus on boolean satisfiability, which to my knowledge, is the most studied problem in computer science. It is not a purely theoretical concept, it has industrial application and it has potential to inspire you for more projects and perhaps help you solve problems in projects you are already working on. We already did demonstrate solving graph problems finds use in level design in games, same could be true for boolean satisfiability or simply problem.

An instance of such problem is a boolean formula expressions written in conjunctive normal form or a clausal form meaning it is a conjunction of clauses and each clause is a disjunction of literals.

A conjunction is logical AND operation denoted above as and disjunction is logical OR operation denoted as . Parentheses indicate clauses which consist of literals where a literal is a symbol pointing a variable or negation of variable. For the CNF expression I picked a set-theoretical description which denotes the set of clauses in which clauses are sets of literals . It is allowed to have more literals than variables.

The easiest way to get started is by playing with small examples. For instance, a expression is an instance of problem when . Such formula has exactly three literals per clause.

Let us computationally solve, personally I use the MergeSat solver. First we write in .cnf format which is accepted by the solver. Each line ends with 0, negative numbers are negations, each line is a clause except for first line which indicates the CNF form with number of variables and number of clauses.

p cnf 3 3

1 -2 3 0

1 2 -3 0

-1 -2 3 0

The CNF formula is satisfiable, output from Mergesat indicating this as well as assignment of values to variables can be found in the MergeSat output. Of course this does not have to be the only solution that satisfies . Now, for contrast, let us consider which will involve two variables and four clauses.

p cnf 2 4

1 2 0

1 -2 0

-1 2 0

-1 -2 0

Unlike in case of the previous form, the is not satisfiable which is indicated by the MergeSat output. It can also be deduced intuitively by looking at clauses of , they list all the possible assignments of values for two boolean variables making it not possible to satisfy a clause without violating another. It is also worth noting that the problem can be efficiently solved in polynomial time (linear) as it is a special case of (Krom, 1967; Aspvall, Plass, & Tarjan, 1979; Even, Itai, & Shamir, 1976)

For now let us ommit the CNF form and define the circuit satisfiability problem in a similar way, a boolean formula is a word of a formal context-free grammar of a form reassembling to the syntax trees involving boolean operators , and with literals as terminal symbols. Formal language is defined by a quadruple where is a finite set of non-terminal symbols, is a finite set of terminal symbols, is a set of production rules and finally is the start symbol.

Worth noting that is a generalization of meaning that every possible is a word of and this is because every boolean formula in conjunctive normal form forms a valid syntax tree described by the .

The circuit is satisfied by an assignment of values to variables . In the case of which involves only a single boolean variable and none of its values satisfies the circuit.

The problem might be the most studied problem so far, the number of available solvers and heuristics is vast and it makes it attractive to formalize our formal satisfaction problems as formulas and take advantage of decades of research and use those solvers to process them efficiently. What about the ? We made a formal argument that every is but what about the other way around?

We could apply DeMorgan’s Law and the distributive property to simplify formula generated by the and eventually rewriting it into CNF form. This unforuntately could lead to exponential growth of formula size. This is where the discovery of Tseytin Transformation (Tseitin, 1983) which is an efficient way of converting disjunctive normal form DNF into conjuctive normal form CNF. We can imagine a sequence of algebraic transformations such as variables substitutions in order to translate an arbitrary into . Problem with that is the number of involved variables would grow quadratically and this is an NP-Complete problem, every extra variable is increasing the number of required steps to solve by an order of magnitude. The advantage of Tseytin Transformation is that CNF formula grows linearly compared to input instance expression. It consists of assigning outputs variables to each component of the circuit and rewriting them according to the following rules of gate sub-expressions.

Where , and are , and classical gates with as a single output. I will not provide a rigorous proof for those sub-expressions, rather provide some intuition, which is if we think of satisfying all the clauses then each of the gate sub-expressions becomes a logic description of the gate consisting of relevant cases, which are clauses, of how the inputs affect the output . Let us analyse clasuses of the gate. Clause indicates that if both and are true, then the only way to satisfy this clause is to assign to true as well, which already seems to implement pretty well. The remaining case to ensure is enforcing to false when at least one of inputs is false and this is done by clauses .

Let us examine an example of circuit converted into problem using Tseytin transformation. The example circuit consists of three inputs , a single output and seven logic gates. Circuit takes the following form.

Note that one of the gates has two outputs. Formula corresponding to this circuit can be written in a predicate form which is recognizable by the which is no longer in CNF form.

Applying the Tseytin transformation to this circuit leads to expression with more variables but in conjunctive normal form. It requires to apply the gate sub-expressions to each of gates of the circuit leading us to following CNF form.

Each of is an individual CNF form corresponding to particular gate of the circuit. The penalty for such convenient notation is in the extra variables that have to be introduced. We can assemble those forms into and the cnf file is also provided.

This circuit outputs true if given one of the following four inputs . We can enumerate all the solutions by appending a clause that is invalid if given a previous solution until the formula becomes unsatisfiable. For instance if we append clauses we will get the following form.

Which is satisfiable only by solutions as assignments have been excluded by the appended clauses. Following this logic the following formula includes clauses from all the solutions and is unsatisfiable. The formula file is also provided.

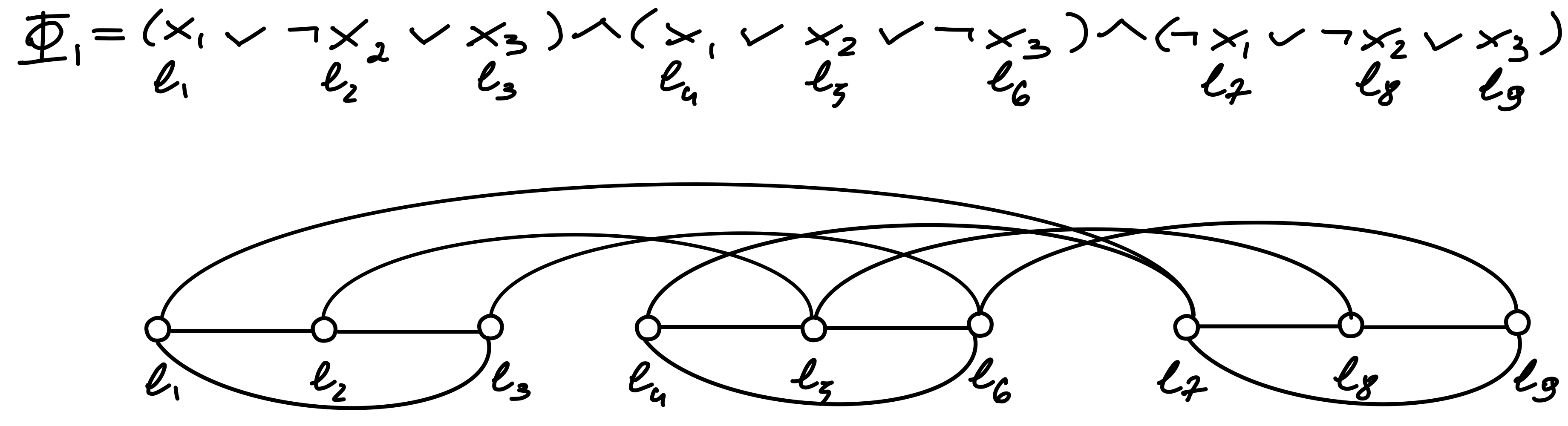

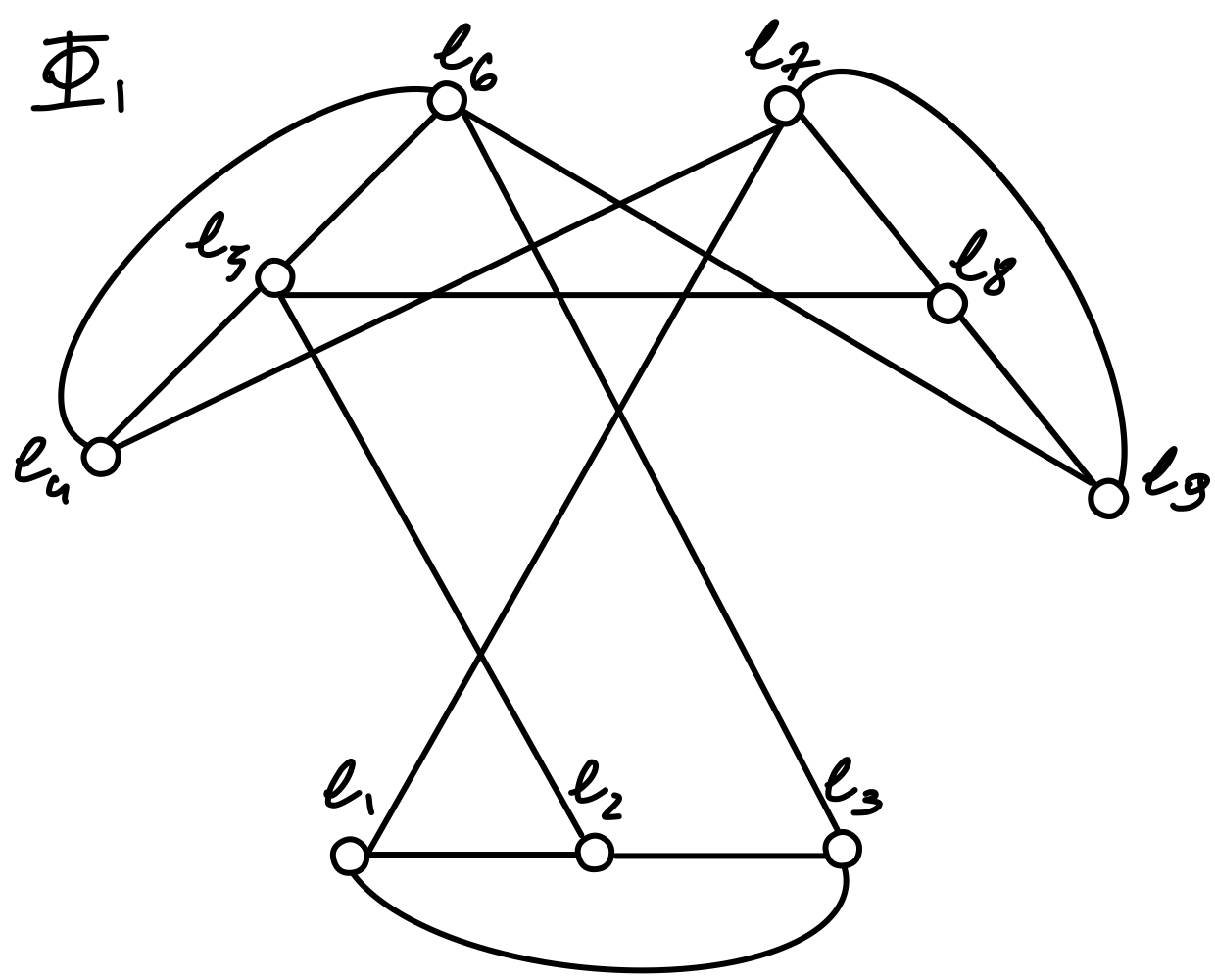

Let be an arbitrary instance formula and we want to find an instance of maximum independent set as defined in Vertex Covers and Independent Sets in game level design. We know both of those problems are NP-Complete thus by (Karp, 1972) there must exist a transformation, or a polynomial reduction which transforms one instance into another in polynomial number of steps in terms of data size. As a brief reminder, the target instance of takes form of a graph where is set of edges of and is a set of vertices of . We construct from according to the following definition.

If the maximum independent set of the graph described above is of size equal to number of clauses of the CNF formula then is satisfiable, i.e . Reason for that is all the literals inside of clause are coupled together making it impossible to select more than one vertex without violating the independent set constraint. The lowest number of violations is zero and this corresponds to exactly one literal per clause.

The process illustrated on figure above consisists of assigning a graph vertex for each literal, then connecting the vertices corresponding to literals of same clasuses with an edge - this creates the clause clusters. Then we join with an edge all vertices corresponding to negation of corresponding variables, those we call conflict links. The graph obtained from the method above can be re-arranged for better aesthetics.

If you read the Vertex Covers and Independent Sets in game level design article you know that maximum independent set problem is semantically equivalent to minimum vertex cover problem thus this reduction can be treated as reduction to either of those problems. Moreover, if you checked the using Quantum Adiabatic Optimization article you know that such problem could be solved using a quantum adiabatic processor, which already reveals one of possible options of solving problems using a quantum machine.

We also can connect this problem to our constraint programming post. The is essentially a predicat and could implement a constraint. Thus an instance of could be used to design a boolean circuit which is satisfied when the instance is satisfied, then via Tseytin transformation we can convert it to CNF formula and even reduce to instance. As long as the domains of variables of your are boolean this should be relatively straightforward process, but once your constraints involve integer domain your circuits would start to look like computer processor circuits, they would involve arithmetic-logic components and grow beyond what is currently trackable.

Another interesting thing we can think about is, as the and instances are described using a context-free grammar determining if any is an instance of boolean satisfiability can be done efficiently by checking if is a word described by . Yet if we introduce a subtle change in the definition and claim that describes only formulas which are satisfiable, suddenly checking if is a word of this grammar becomes computationally hard problem. My conclusion from this is quite direct and philosophical - that finding an example of a hard problem is equivalent of solving a hard problem.

This blog post barely scratches the surface of decades of research on the concept of satisfiability and logic programming, but it does provide the necessary definitions and gives us foundations to proceed to many other interesting concepts. One possible direction I consider at the moment of writing this post are hashing functions, cryptography and blockchains, another one is computational complexity theory and yet another one is formalizing satisfiability of circuits from category-theoretical perspective. If you have any preferences regarding the direction this blog goes or if you have any questions or find errors or typos please do not hesitate to let me know via Twitter or GitHub. All the .cnf files from this post are available in this public gist repository.

- Krom, M. R. (1967). The Decision Problem for a Class of First-Order Formulas in Which all Disjunctions are Binary. Zeitschrift für Mathematische Logik und Grundlagen der Mathematik, 13(1-2), 15–20. 10.1002/malq.19670130104

- Aspvall, B., Plass, M. F., & Tarjan, R. E. (1979). A linear-time algorithm for testing the truth of certain quantified boolean formulas. Information Processing Letters, 8(3), 121–123. 10.1016/0020-0190(79)90002-4

- Even, S., Itai, A., & Shamir, A. (1976). On the Complexity of Timetable and Multicommodity Flow Problems. SIAM Journal on Computing, 5(4), 691–703. 10.1137/0205048

- Tseitin, G. S. (1983). On the Complexity of Derivation in Propositional Calculus. In J. H. Siekmann & G. Wrightson (Eds.), Automation of Reasoning: 2: Classical Papers on Computational Logic 1967–1970 (pp. 466–483). Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg. 10.1007/978-3-642-81955-1_28

- Karp, R. (1972). Reducibility among combinatorial problems. In R. Miller & J. Thatcher (Eds.), Complexity of Computer Computations (pp. 85–103). Plenum Press.