Trustless Mimblewimble transaction aggregator based on scalable BFT

Share on:This article is a proposal for a trustless transaction aggregation protocol for grin - a privacy-preserving digital currency built openly by developers distributed all over the world. The protocol introduced in this work is based on the concept of Byzantine Fault Tolerant (BFT) consensus and takes into consideration problems of scalability and security. It is going to be a significantly longer article than usual as all the concepts needs to be introduced before suggesting a solution.

Contents

Introduction

Grin is a privacy focused digital currency based on the innovative blockchain protocol called Mimblewimble (MW) introduced by Tom Elvis Jedusor. The innovation of MW is capability of storing transactions on the block without storing addresses and without revealing the amounts. For MW based blockchains privacy is built in the protocol. It relies on the Elliptic-curve cryptography (ECC) which has already been briefly introduced on this blog. We will (very briefly) discuss how MW transactions work and for more detailed description reading the whitepaper is recommended.

Grin transactions can be merged (or aggregated) into larger transactions. This is possible as MW protocol only requires the verifiers to ensure if net change is zero. An idea for a daily aggregator has been proposed. Such system would improve privacy by making it harder to reconstruct transaction graph by analyzing the blocks. Due to this problem grin has been accused of being broken and official response to this claim has been issued.

The daily aggregator, although would drastically improve privacy, it would also introduce a central component in a network which by definition is not supposed to be centrally controlled by anyone. For that reason a challenge for a trustless aggregator has been opened and this article is a modest proposal for that challenge. Such trustless aggregator would not be centrally controlled by anyone and it would still address the transaction linkability problem in a same way as the daily aggregator.

The solution I propose here is based on the Byzantine Fault Tolerant (BFT) consensus, which very generally, describes an approach of executing a state machine replicated over a larger collection of nodes in parallel. What makes it Byzantine is ability to deal with possible software or hardware faults of the nodes executing the state machine, possibly even malicious behaviour done purposely. The name refers to the Byzantine generals problem (Lamport, Shostak, & Pease, 1982). Nodes executing the state machine need to reach consensus on which state the state machine has to transit into. Several solutions have been proposed, first one suggested in (Castro, Liskov, & others, n.d.), few of the famous and more modern ones are Prime (Amir, Coan, Kirsch, & Lane, 2011), Aardvark (Clement, Wong, Alvisi, Dahlin, & Marchetti, 2009) or Spinning (Veronese, Correia, Bessani, & Lung, 2009). There are many of them and there is no point listing them all. For this proposal I picked one named Proteus (Jalalzai, Busch, & Richard, 2019) which apart from reminding me of Proteus IV - a killer computer from 1977 American science fiction–horror film and 1973 novel by Dean Koontz - is a recently proposed protocol and has an attractive scalability compared to other solutions I considered.

Compared to the proof of work (PoW) BFT has advantages as well as disadvantages. It is more energy efficient, has transaction finality - transactions do not require multiple confirmations - and has low reward variance, which means that it is possible to more fairly distribute rewards to processing nodes. Majord disadvantage compared to PoW are scalability as BFT solutions require quadratic number of exchanged messages to reach consensus. Another issue is susceptibility to Sybil attacks. The aim of this work is not take sides on which of the solutions is better. I would advocate for the right tool for the right job kind of approach. The design will be discussed in more details in the further sections of this article, but in great simplification I suggest to use BFT public cluster of nodes to perform transaction aggregation for grin.

Trustless aggregation problem

In this section basic theory of Mimblewimble transactions will be provided as well as a quick review of how the scalable BFT protocol operates and eventually I will put this concept in the context of transaction aggregation.

Mimblewimble

The Mimblewimble transaction is encoded using ECC algebra. If you are not yet familiar with this concept I highly recommend you to check the brief introduction and play around with it. I will not go too deep into that in this section. Only a very brief overview of Mimblewimble will be provided and it will be based it on the official grin documentation. It also relies on the idea of commitment so I also recommend to quickly check it.

Let the public key be a sum of two private keys and applied to a curve generator point , we know the following ECC property holds

and it is a condition for the MW transactions to be valid. Such transaction only requires two properties to be proven (i) zero sum - the net change in amounts involved in the transaction must be zero. Another one is (ii) possession of private keys - which I would rather to refer to as the output ownership. It means that one who owns the output is one who has the associated private key.

It is possible to verify that transaction sums to zero without knowing the actual amounts by introducing an another generator point on the curve - . For the purpose of this example let be the input of the transaction and and be the outputs of the transaction. One can verify that

Knowledge of the actual amounts is not required to verify the validity of the above statement. Usually transactions have similar amounts and range of those values is narrow. Performing simple brute force would one allow to find often recreate exact amounts with high success rate. Solution to that issue is to take advantage of entire space of the ECC finite field and distribute curve points of the transaction more randomly. This is achieved using blinding factors which are additional points points on the curve associated to each amount generated by a different generator point . With the blinding factors , and the above transaction becomes

The value on the right hand side is a publicly known commitment. Now in order to prove net value of the transaction is zero one must subtract from it which is the public key of the transaction. The value is the shared private key. Such public key shall be signed by the participants of the transaction using a collective - Schnorr’s signature to prove their ownership of the transaction. A properly signed public key is called the transaction commitment and together with the signature it is called a transaction kernel.

An important property of the kernels is that they can be constructed by anyone. What makes a single transaction valid makes also entire block valid - the net value must be zero. A property relevant to this article is that by adding the transaction kernels we preserve this zero sum property and this allows transactions to get aggregated into larger transactions.

Scalable BFT

Until here it has been briefly discussed how MW transaction get encoded on the ECC curve finite field and how they can be aggregated. Now another relevant concept will be introduced - the brief introduction to BFT protocol.

The Byzantine generals problem considered in (Lamport, Shostak, & Pease, 1982) consisting of number of generals commanding divisions of an army and communicating via a messenger. It is assumed that some of those generals could potentially be traitors who are willing to sabotage the war plan. All the generals need a strong majority agreeing to attack to succeed with their plan. For this two essential properties need to be satisfied: (i) all loyal generals must agree on the same plan and (ii) a small number of traitors must not be capable of changing mind of the loyal generals. It is also assumed that the loyal generals would stick to the plan and traitors could do anything they wish to do.

The problem that has just been described is the essence of the idea of consensus. Any public distributed system is susceptible to such Byzantine participants who wish to join and wish to disrupt its behaviour. Lamport has proven in his work (Lamport, Shostak, & Pease, 1982) that consensus can be achieved if at least nodes are honest. Here the value represents the number of such Byzantine participants for which it can be assumed that unpredictable and even malicious behaviour could occur.

The protocol considered in this article - scalable BFT Proteus introduced in (Jalalzai, Busch, & Richard, 2019) operates by randomly electing a subset of participants among known as the root committee. Those participants are the nodes performing actual computation, which in case of this work is transaction aggregation and keeping track of MW mined blocks. The remaining nodes are called replica nodes and they sync state with the root commitee.

It is the root committee that is in charge of reaching consensus of state. Remaining nodes are the judges of the matter if the consensus has been reached or not. If yes, replica nodes sync with the proposed state, otherwise they enforce committee re-election which the authors refer to as the view change. In order to reach approval, the root committee needs to collect at least digital signatures. Once approved state can be synced across the replica nodes. Such algorithm would reach consensus and operate correctly as long as there is less than Byzantine nodes. The overall number of Byzantine nodes tolerable in the cluster obeys the theoretical threshold for reaching the consensus .

Another advantage of scalable BFT is that the most of the communication is done within the root committee. The remaining nodes only verify the state which leads to a more attractive communication complexity . Within the regime characterized by large number of replica nodes compared to number of members of the root committee, i.e the quadratic term gets dominated and the message complexity becomes . In the future this complexity is intended to improve even further as the authors of this scalable BFT protocol currently search for improvements of scalability by implementing sharding.

This overview was brief but sufficient to grasp an overall idea of how the scalable BFT operates. For more details reading the cited paper is recommended. It provides the algorithms in pseudo-code as well as it refers to an implementation of the protocol in the Go programming language.

Trustless aggregator

So far the basics of MW and BFT have been briefly explained. Current section is meant to combine that knowledge and draft a protocol for a large BFT cluster capable of aggregating grin transactions in trustless way.

Aggrematon

When BFT cluster computes and syncs a state across its network of nodes it implements a model of computation formalized using the state machine. This allows to separate logic of computed decentralized program from the BFT protocol itself. There are many known abstract machines, from simple ones such as the Finite State Machine (FSM) up to complex ones such as the Turing Machine (TM). Each has different capabilities indicated by which formal grammar the abstract machine is capable of recognizing. There is a whole hierarchy of those abstract machines, as well as formal grammars they are capable of accepting and the field of science that studies their properties is refered to as the Automata Theory.

For the purpose of this article it is not required to go deep into that as this work does not require to formally prove that some problem is computable nor it does not require for searching of computational complexity of any algorithm. In the context of BFT the abstract machine is merely a way to represent the program that must be computed by the cluster. For that reason the regular formalities of the automata theory are not going to be strictly followed in this proposal.

In plural it is correct to say automata and singular for it is an automaton. Since the objective is finding an abstract machine for aggregating transactions it seems accurate to call it an aggrematon for an aggregating automaton. That is for the design of the abstract machine, for an actual implementation, i.e a node that is aggregating transactions would be called an aggregator. Under this terminology, the BFT cluster would be build out of the aggregators and each of them would implement an aggrematon. As for the abstract machine, since the transaction aggregation is not only recognizing its given input (an incoming transaction) but also producing an output (aggregating it into a larger chunk of transactions which we will refer to as an aggregate) an state transducer appears to be a good starting point. Such transducer is a sixtuple of the form

where is an input alphabet indicating input data - for instance incoming events. Then is an output alphabet indicating possible responses from the machine. Then is a set of states machine can be in and is its default initial state. Finally is a morphism indicating the transition between states and is the response morphism, indicate what machine responds and when. Normally it would be assumed that the alphabets and are finite, yet for purpose of this article such requirements will be relaxed. This abstract machine is going to be equipped with just a single state which permits to immediately define

The input alphabet would consist of four words spanned by an infinite possible number of incoming transactions and new blocks reported by the regular MW nodes. This leads to

where indicates that there is no new block in the MW blockchain nor incoming transaction. Then indicates that there are no incoming transactions yet there is a new block, an example incoming word could be where indicates the newly created grin block of height . Whenever a new transaction is received but there is no new block the aggrematon would recognize a word of the form where is the incoming transaction to be aggregated and represents requested block height until which the sender wishes the aggregation process to persist. Finally means there is a new transaction and new block, note that as it is not possible to append any information to already created block. Now for the output alphabet, it is generated by two words and and also we introduce a new set representing all the possible aggregates.

For example indicates that the aggregate should be broadcasted and included to the nearest block. The word indicates transaction shall be aggregated to an aggregate . For the case of this machine, the state transition morphism is really trivial

as it always leads to exactly same state . The essence of this machine lays in the -morphism as this is what encodes the actual behaviour of the machine - how it responds to different inputs.

In the order of appearance, first case covers possibility of not having any transactions and also not receiving any information about new blocks. It covers the scenario of dystopian future in which entire MW network stopped and for some mysterious reasons the aggregation cluster is still listening. Technically it tells -morphism to do nothing, seems pretty useless yet for the sake of having an identity operation it should be included. The second one tells the machine that block height has been reached and nothing more is going to get aggregated to the aggregate and it should be posted to the mempool to be included to the nearest block. It can be assumed only the root committee members would post the transaction, verifiers would only check if it appears in the mempool. Third case represents receiving a new transaction and aggregating it to the aggregate . Finally last one is an ambiguous case when there is both new block and also new transaction, in such case we have to choose a convention, here it has been decided to prioritize posting aggregates over aggregating. It is important to cover such case to not let the machine become non-deterministic.

This completes the draft of transaction aggregating abstract machine.

Adapted scalable BFT

Authors of (Jalalzai, Busch, & Richard, 2019) considered nodes with a special subset of nodes to perform computation. Various scenarios of failure have been considered and tested. Yet as for a popular project like a grin, a MW-based cryptocurrency it is reasonable to imagine many people would like to join the network and try to have their device become part of replica nodes or a root committee nodes. From the plots in (Jalalzai, Busch, & Richard, 2019) it seems like at around processing the state machine becomes inefficient. Scalable BFT was able to process around one single transaction per second at this stage. It would be beneficial to build even larger network by allowing a greater set of nodes to join in with privileges lower than verification nodes.

Candidates pool

This is where the original Scalable BFT is slightly modified by introducing an additional set of nodes to the cluster. Those additional participants are refered to as the candidates pool of size . Nodes in the candidates pool would not need to sync the state with verifying nodes to not worsen the message complexity, however they would need to provide proof of being reachable via a sort of heartbeat protocol. This should provide enough room for everyone who wishes to join the aggregation network. Assuming the cluster would take nodes as it was experimentally studied in (Jalalzai, Busch, & Richard, 2019) the total cluster size with the candidates pool would be of size over which should provide enough capacity for anyone willing to join the cluster.

Deposits

Another motivation for introducing the candidates pool is protection against the Sybil attacks. Such attack would consist of creating large amounts of Byzantine nodes in order to manipulate the information flow. In case of the regular MW network what protects it from manipulating the consensus is a strong memory intensive PoW algorithm based on the cuckoo cycle. Creating MW miners costs real life resources - graphic cards with high memory. As for aggregation cluster, I imagine it as a network anyone could join in, even using a modern mobile phone during regular usage without disturbing its functioning. The idea for protecting the cluster against Sybil attacks consists of introducing deposits. Every node in the cluster, including the candidates, would be identified by public key and thus also a MW address. A node would be accepted in the network only if grins are signed by this node as recipient and locked until block height . This why it is called a deposit, because it is refundable minus processing fees. This forces all the participants to freeze some resources temporarily in order to join the cluster. If is sufficiently large, a potential attacked willing to conduct a Sybil attack on this network would need to temporarily allocate huge amount of grin coins to create sufficient amount of Byzantine nodes in the candidate pool. Later in the Security section I briefly analyze probability of successfully conducting such attack. Another interesting idea would be to make fluctuate and adapt to current network state, for example it could change every time view change occurs et cetera.

It might be possible to make it more radical and permanently destroy deposit grins and make it just costly and non-refundable to join the network. It would be closer to PoW approach yet without rewards. This solution seems very flexible and it is encouraged to brainstorm more ideas.

Discussion

Until here, basic theory required to build scalable BFT computing clusters has been introduced. Also, the foundations of MW protocol has been briefly discussed. Based on those two concepts an abstract machine for aggregating MW transactions in the scalable BFT network has been proposed. Also, some ideas for how to protect such network from Sybil attacks as well as making it more inclusive have been introduced. In this section a brief discussion on those concepts will be conducted, particularly regarding the matters of security, practical implementation and scalability.

Security

Earlier an idea for protecting the cluster from the Sybil attacks by introducing refundable deposits has been proposed in the Deposits section. It operates by introducing a temporary cost to join the cluster. The overall number of nodes has also been expanded by an order of magnitude by introducing the candidates pool in the Candidates pool section. The paper (Jalalzai, Busch, & Richard, 2019) does discuss security of scalable BFT cluster, here a further will be provided to take into account the modifications mentioned above.

The process of random nodes joining the cluster from one pool into another can be probabilistically represented using the urn problem. For instance, let be an event of drawing red and white balls from an urn containing red balls and white balls. So the total number of balls drawn from the urn is and total number of balls in the urn is . The probability of is given by the hypergeometric distribution

A potential attacker will be interested in knowing how many Byzantine nodes he or she has to implant in the candidates pool to reach certain probability of getting them into set of verifying nodes. Equally, he or she might be interested in knowing how many Byzantine nodes he or she might need among the verifying nodes to get certain number of Byzantine root committee nodes if the view change occurs. This can be modelized using the urn problem by calculating the probability of drawing certain number of red balls from the urn which contains particular number of red and white balls. This is also how the authors of (Jalalzai, Busch, & Richard, 2019) estimated it in their equation (1). In this article the scalable BFT protocol has been modified and now also the candidates pool has to be considered. A slight modification to the model has to be introduced. Imagine a certain number of red balls and of white balls has to be drawn from the first urn which contains balls and of them are red. The first urn represents candidates pool, the drawn red balls managed to enter the set of replica nodes. The ball drawn from first urn are placed in the second urn and we draw again, this time we draw red balls and white balls from the urn containing balls where are red and are while. Balls drawn out of the second urn represent nodes entering the root committee after the occurrence of the view change. This event is denoted by and given that its probability magnitude is

In order to estimate probability of getting Byzantine nodes entering the root commitee given the attacker has implanted Sybil nodes in the candidates pool it must be considered all possible pairs and which sum up to , the event representing such attack is denoted by and its probability magnitude is

To wrap it together, the attacker would want to have more than Byzantine nodes in the root committee to disrupt the consensus, getting this number of nodes given the candidates pool has Sybil nodes we define an attack event and its probability is

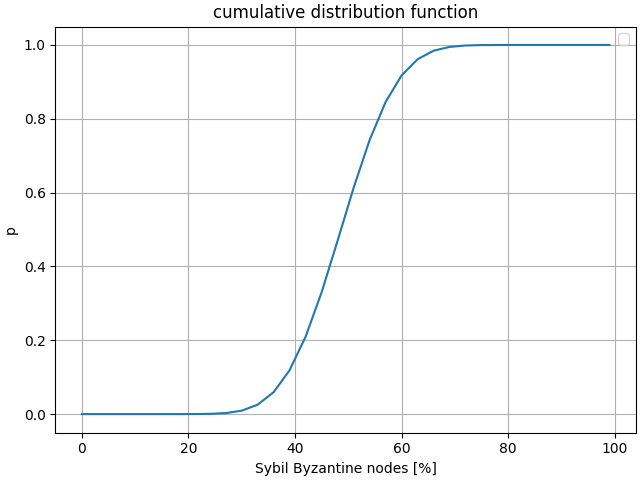

The plot of is a visual representation of the cumulative distribution function with on the horizontal axis.

The above plot shows a probability of successfully introducing more than Byzantine nodes into the root committee given that the candidate pool has certain proportion of nodes (represented by horizontal axis). Data used for the plots correspond to scenario of verifying nodes with candidate nodes. Root committee of size , to disrupt consensus Byzantine nodes need to be introduced. If you are interested in trying different values I encourage you to run my script available in this public gist repository.

The cumulative probability distribution takes the sigmoid shape which indicates it corresponds to a normal distribution which intuitively makes sense as the most significant improvement in probability would occur once certain threshold of Sybil nodes gets trespassed, after that improvement is less significant.

The cost in terms of deposit of such attack is difficult to estimate, for that it would be required to theoretically calculate an expected number of view changes to reach Byzantine nodes in the root committee. It should also be taken into account that Sybil nodes could be introduced one by one if some of the nodes among the verifying nodes time out and need a replacement from the candidates pool. If this idea gains interest in grin community we can invest time to create a more elaborate probabilistic model to study such scenarios.

Implementation

An advantage of this approach is the possibility of implementing it in scrum approach by delivering a usable product at each stage of development without the need of immediately dedicated huge amount of resources to implement the end product. I suggest to implement it in three stages: daily aggregator stage, then trusted network aggregator stage and finally trustless aggregator final stage. Each of them taking advantage of experience gained while building the previous one. Let me guide you through the process step by step.

The initial step would consist of implementing the machine described in Aggrematon section in Rust programming language wrapped in a minimalistic Application Programming Interface (API). This would already deliver value to the grin community as it could work as the daily aggregator proposed by @oryhp.

Next stage would consist executing this machine inside of a consensus algorithm designed for trusted networks such as raft protocol (Ongaro & Ousterhout, 2014) which would allow to execute it in parallel yet without protection against the Byzantine nodes. There already is more than one Raft implementation in Rust programming language which would facilitate this step. At this stage we would have an aggregator running as cluster of nodes syncing state in parallel. It would have to be a trusted network as Raft does not provide protection against malicious nodes that could show Byzantine behaviour.

For the last stage implement of the scalable BFT proposed by (Jalalzai, Busch, & Richard, 2019) would be required by translating their Go code base into Rust programming language to match the rest of grin code base conventions. It would also consist of implementing the protocol modifications I briefly drafted above - candidate pool and deposits. If successful it would work as a trustless aggregator of grin MW transactions requested in here.

As you probably noticed, the BFT implementation does not rely at all on any details regarding MW. The efforts of building this system as open-source software under some non-restrictive licence could kickstart the economy around grin as it could be used to build different trustless grin-based services. Such BFT clusters could store and verify various scriptless scripts and implement various services such as bounty programs, funding applications, exchanges et cetera. All one has to do is replace the aggrematon mentioned in Aggrematon section with a different abstract machine, the rest of the stack would be re-usable to build a completely new grin-based decentralized application (dApp). At least as long as he or she manages to convince sufficient amount of users to run nodes that could join the newly created BFT cluster dedicated for this dApp.

Scalability

One of main concerns of BFT clusters is their poor scalability. In case of scalable BFT mentioned in this article this problem has been improved but not completely resolved. The authors of (Jalalzai, Busch, & Richard, 2019) considered and experimentally tested a scenario of nodes with root committee of size and managed to process around one transaction per second in their blockchain scheme. It has been tested by running such amount of nodes on Amazon EC2. If an assumption is taken that the cluster of this size could aggregate a single transaction per second it is still far away from matching the theoretical capacity of grin cryptocurrency.

Given that grin has a limited maximum block weight by taking into account average transaction would be inputs, outputs and kernel as estimated here per block transactions in average could occur. One grin block is created every minute, which implies that with a single aggregation per second it could aggregate transactions which is roughly % of theoretical capacity of grin.

Fortunately it is possible to run more than one cluster to balance that load. All of the BFT clusters could share same candidates pool as it is order of magnitude larger than the set of replica nodes. With around of such clusters it should be possible to match the maximum capacity of grin. At least in average and it is a very rough estimate.

Each of the nodes would need to store public keys and signed transactions of each of other nodes. The state to be synced would be much smaller as it would consists of certain number of future aggregates, say for next hours and one per hour. The memory impact of such node should be in megabytes and as there is no need for any PoW. If this estimate is accurate then even an older generation smartphone could serve as an aggregator in such network.

Conclusion

The scalable BFT protocol used as a foundation for the trustless aggregator proposed in this work has been experimentally tested on large amount of Amazon EC2 nodes. I briefly discussed how to use it to aggregate MW transactions for the grin cryptocurrency by implementing an aggrematon - an automaton for aggregating transactions - and that has been discussed in section Aggrematon.

I introduced an idea for order of magnitude larger set of nodes called the candidate pool it was discussed in the Candidates pool. As drafted in the Scalability section, the memory impact of an aggregator node would be small, there could be potentially large number of users interested in joining it thus candidate pool would also provide enough room for them making the cluster more inclusive.

Due to low memory impact of those aggregating nodes there is a high risk of Sybil attacks. To prevent that I suggested refundable deposits required to join the network which could at least partially solve this problem. This has been discussed in Deposits section. The algorithm itself is flexible and more violent means could be implemented such as (if theoretically possible) permanently destroy coins paid by the node to join in case if such node gets proven of certain Byzantine behaviour. In section Security I briefly discussed the probability of introducing sufficient amount of nodes into the root committee of the BFT cluster from the candidates pool.

The solution proposed here is not very MW related. The disadvantage of that is likely it is not the most efficient way of achieving the trustless aggregator, however the advantage could be re-using this implementation to build different trustless decentralized application on top of the grin cryptocurrency. This has been discussed in Implementation section. It also discussed a scrum approach of building this prototype in order to save resources on the way and at each stage deliver something valuable to the users.

The requirement of operating on layer 1 has not been addressed in this article due to my lack of appropriate definition what this exactly means. Further discussion is essential to address that.

This proposal is not very strict. Certainly more theoretical and practical details are required, as well as the solid peer review process. For that purpose I open a thread in the grin Forum. Please feel free to provide your feedback there. I will gladly discuss this idea and adjust this article accordingly.

Almost six months later I get back to this proposal to clarify that this idea was missing two essential solutions: how to ensure outputs get locked during the process of aggregation to prevent double spending, and also how to prove the outputs exist to the aggregating nodes of the BFT cluster. Perhaps someday we could think of it again.

References

- Lamport, L., Shostak, R., & Pease, M. (1982). The Byzantine Generals Problem. ACM Transactions on Programming Languages and Systems, 4(3), 382–401. 10.1145/357172.357176

- Castro, M., Liskov, B., & others Practical byzantine fault tolerance.

- Amir, Y., Coan, B., Kirsch, J., & Lane, J. (2011). Prime: Byzantine Replication under Attack. IEEE Transactions on Dependable and Secure Computing, 8(4), 564–577. 10.1109/tdsc.2010.70

- Clement, A., Wong, E., Alvisi, L., Dahlin, M., & Marchetti, M. (2009). Making Byzantine Fault Tolerant Systems Tolerate Byzantine Faults. In Proceedings of the 6th USENIX Symposium on Networked Systems Design and Implementation, NSDI’09 (pp. 153–168). USA: USENIX Association.

- Veronese, G. S., Correia, M., Bessani, A. N., & Lung, L. C. (2009). Spin One’s Wheels? Byzantine Fault Tolerance with a Spinning Primary. In 2009 28th IEEE International Symposium on Reliable Distributed Systems. IEEE. 10.1109/srds.2009.36

- Jalalzai, M. M., Busch, C., & Richard, G. G. (2019). Proteus: A Scalable BFT Consensus Protocol for Blockchains. In 2019 IEEE International Conference on Blockchain (Blockchain). IEEE. 10.1109/blockchain.2019.00048

- Ongaro, D., & Ousterhout, J. (2014). In Search of an Understandable Consensus Algorithm. In Proceedings of the 2014 USENIX Conference on USENIX Annual Technical Conference, USENIX ATC’14 (pp. 305–320). USA: USENIX Association.