Vertex Covers and Independent Sets in game level design

Share on:I wanted to write something fun related to optimization since the moment of my graduation. In this article I will introduce you to few basic concepts in the graph theory, the vertex cover and independent set. By showing you how those can form decision problems and optimization problems, we will discover how useful they could be in modelling and solving practical problems in game level design. As an example, we will introduce a problem of placing Pokémon Centers and Pokémon Gyms on the map of Kanto region from the classic Pokémon games!

I always loved to play Pokémon games, I do it until this day. The Pokémon-related optimization problem is mostly meant to entertain you a little bit while trying to learn some optimization, however it could (and I hope it will!) inspire you to try to use such optimization techniques for various design problems, such as in case of this article it is a game map design problem. This connects the optimization to the procedural content generation, often used in game design. After reading this article you can think of some other design problems which could be modelled as graphs.

Let us begin with the definitions. A vertex cover is a subset of vertices of a graph such that every edge of that graph has at least one of its endpoints included in the vertex cover

As a decision problem, the vertex cover problem accepts a graph and a positive integer and determines if there exists a vertex cover of of size at most , which is the NP-Complete problem formulated in (Karp, 1972). As an optimization problem, the the minimum vertex cover problem, given a graph finds the smallest possible value such that a vertex cover of of size exists.

An independent set is a subset of vertices of a graph such that no two of such vertices are connected with an edge.

In a way similar to the vertex cover problem, a NP-Complete decision problem called independent set problem can be formulated, accepting a graph and a positive integer and finding if an independent set of size exists for the graph , and as you might expect, an optimization problem called maximum independent set can be formulated which finds the largest possible value of for a given graph .

Both vertex cover and independent set compliment each other, meaning that if we find one of them, we automatically have another for free!

Of course, for each vertex cover there exists a unique independent set and vice-versa, its not as any random two vertex cover and independent set could complete each other. What follows from that is the minimum vertex cover complements the maximum independent set. It makes sense, a most trivial vertex cover is a set of all the vertices and it corresponds to the most trivial independent set being an empty set .

It is too little to be called a proper proof, but rather a formal argument. Let be an edge from the graph and let us keep in mind the , we find the following.

What I mean by that is violation of vertex cover implies the violation of independent set and vice-versa, because an edge that is not covered by one of its connected vertices, which violates , in the compliment set corresponds to both vertices of the same edge being selected, which is exactly the violation of the definition .

Mathematically speaking, those two problems are closely related. Somehow still, I feel biased towards the maximum independent set, it somehow feels more natural to me to reason using the independent sets. What about you? Do you have any preferences? Feel free to let me know on Twitter!

Now, let us have a look at how those two problems could be used to model some game design problems, in this case, finding locations for Pokémon Centers and Pokémon Gyms in the Kanto region. Those of you who played Pokémon games know that Pokémon Centers are located pretty much everywhere, but for the purpose of this problem, let us imagine that it is long time in the past of the Pokémon history and in those times Kanto region was poor and could not afford to build a Pokémon Center in every town. Our optimization problem states as follows.

The poor region of Kanto cannot afford to place a Pokémon Center in every town, overall number of Pokémon Centers in the whole region has to be minimized but we need every route to be connected to at least one location with Pokémon Center to help trainers cure their Pokémons during their travels. To make the game harder, the Pokémon Gyms must not be placed at the town that contains a Pokémon Center, also no two Pokémon Gyms can be connected by a direct route.

This problem maps directly onto minimum vertex cover problem, in which the Kanto region map becomes graph , set of all towns is a set of all vertices , all the routes connecting the towns become edges and set of towns with Pokémon Center are represented by the minimum vertex cover of the graph , and set of towns with Pokémon Gyms are represented by the maximum independent set of .

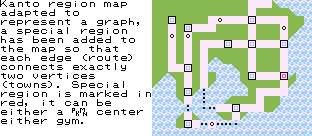

In order to have the Kanto region map be representable as graph , we had to include a Special Region to prevent having routes connecting to each other without having a location at the intersection.

We are going to base our implementation on Python’s frozenset’s as it makes it hashable to embed sets within sets. Let’s make an alias for frozenset, from now on it will be f.

f = frozenset

A simple graph of three vertices, all connected could be build as follows.

V = f({'a', 'b', 'c'})

E = f({f({'a', 'b'}), f({'b', 'c'}), f({'a', 'c'})})

G = (V, E)

We will build a recursive brute-force tool to explore all possible solutions and search for all minimum vertex cover. Such function is non-deterministic, needs to check all possibilities, for this check we can write a function which applies definition directly.

def isVC(sol, G):

V, E = G

cover = set(sol)

for edge in E:

if len(list(edge.intersection(cover))) == 0:

return False

return True

The recursive brute-force function will explore all the execution trees bounded by distance from root to leaves being at most as long as number of vertices of input graph . This search function keeps track of size if currently explored solution (as we search for minimum) and will take take into such consideration only those partial solutions which are vertex covers tested using isVC(sol, G).

def solveAll(sol, idx, minT, C, G):

lst = []

min = int(minT)

if isVC(sol, G):

size = len(sol)

if size < min:

lst = [sol]

min = size

if idx < len(C):

# try to include the next element and see what happens...

lstL, minL = solveAll(sol + [C[idx]], idx + 1, min, C, G)

# try to skip the next element and see what happens...

lstR, minR = solveAll(sol, idx + 1, min, C, G)

# whatever turned out to be better...

if minL < min:

lst, min = lstL, minL

elif minL == min:

lst += lstL

if minR < min:

lst, min = lstR, minR

elif minR == min:

lst += lstR

return lst, min

This function does not have an impressive computational complexity as it solves the problem in where but for the purpose of this article is to show how those problems can be used for modelling, not how to efficiently solve them. For this perhaps you could check the networkx library to get approximate solutions for large graphs really fast.

At this stage we can define the Kanto map in form of a graph. If you look at the map as it was introduced in the game you will see it is not a graph as there is an intersection of routes, which in graph paradigm would imply existence of edges connecting without a vertex. As we already mentioned earlier, to solve it we included a special region marked using red colour in the above figure.

Vertices of the graph are the towns, the in-game locations in general, along with the special region.

V = f({

'Indigo Plateau',

'Pallet Town',

'Viridian City',

'Pewter City',

'Cinnabar Island',

'Cerulean City',

'Saffron City',

'Celadon City',

'Lavender Town',

'Vermillion City',

'Fuschia City',

'Special Region'})

Edges of the graph are all the routes, we do not need to name them explicitly, instead, it is sufficient to indicate which locations are connected.

E = f({

f({'Indigo Plateau', 'Viridian City'}),

f({'Pallet Town', 'Viridian City'}),

f({'Viridian City', 'Pewter City'}),

f({'Pewter City', 'Cerulean City'}),

f({'Cerulean City', 'Saffron City'}),

f({'Saffron City', 'Celadon City'}),

f({'Celadon City', 'Fuschia City'}),

f({'Fuschia City', 'Special Region'}),

f({'Fuschia City', 'Cinnabar Island'}),

f({'Vermillion City', 'Special Region'}),

f({'Cinnabar Island', 'Pallet Town'}),

f({'Saffron City', 'Lavender Town'}),

f({'Lavender Town', 'Cerulean City'}),

f({'Lavender Town', 'Special Region'})

})

We have everything we need to assemble the vertices and edges into graph and apply the solver on it to find the minimum vertex covers via brute-force enumeration. The minT parameter has to be initiated with a big number (strictly larger than number of vertices) to make sure our solver does not neglect candidate solutions.

G = (V, E)

lst, min = solveAll([], 0, 9999, list(V), G)

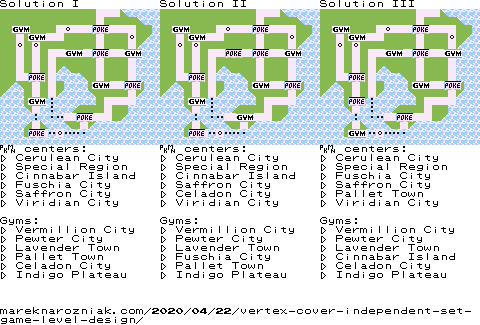

In the output, lst contains the optimal solutions and min is the size of the minimum vertex cover. For the Kanto map problem as we defined it, four solutions exist, they are all of size

Each solution is a set of locations where Pokémon Center is to be built, it is a vertex cover, if you visually examine the above figure, you will see every route has connects at least one Pokémon Center. From definitions of and , it is allowed to have two Pokémon Centers next to each other, but it is not allowed to have two gyms connected, and indeed our solver found only solutions that satisfy this criteria.

Intuitively, in this model, the smaller the vertex cover the larger the independent set, the fewer Pokémon Center, the more Pokémon Gyms. You could relax the requirement of finding minimum vertex cover to make the game easier, providing more Pokémon Center and fewer Gyms.

This is just a particular example, but in your own model for your own game, you would split the vertices of your graph (game map or game level) into two categories, first being something that helps the player (Pokémon Centers are healing Pokémon), could be healing potions, save game check points etc. The other category would be anything that makes the game harder, such as enemies, bosses, traps, obstacles etc. Then based on the effect you want to achieve, you would assing one of category to vertex cover, the other one to independent set and then using the graph optimization techniques you could generate game levels with predictable difficulty. You could include the solver in your game engine as a sort of procedural content generation engine and generate random levels of increasing difficulty as players get more experienced.

There are couple of other interesting things to think about after reading this article. Regarding the solving strategy, you probably tried to solve the instance of our problem mentally by looking at it. What was your strategy? Was it anything better than just trying different covers until one could works?

Other than that. Our solveAll function is naive and not very elaborate, how would you improve it? Is there a straightforward way to modify it to list all the possible minimum vertex covers? I will leave you there and if you have any comments, spot some errors or just want to discuss feel free to Tweet me!

- Karp, R. (1972). Reducibility among combinatorial problems. In R. Miller & J. Thatcher (Eds.), Complexity of Computer Computations (pp. 85–103). Plenum Press.